Being a developer on support

Posted on 31 August 2014

One of the things that gets talked about a lot in the devops world is that developers should support the applications that they build. However, something I’ve seen is developers getting severe culture shock from their first experience of support. Support work is a totally different style of work from ordinary development, and there’s often little or no explanation or instructions as to what you should be doing, and how you should do it.

The first problem: interruptions

Ordinary development work eschews interruptions. You work on hard problems that often don’t have immediately obvious solutions (or worse, have immediately obvious wrong solutions). You may need to go through several iterations of design before finding one that solves the problem adequately. You hold a lot of context in your head, so an interruption can be incredibly disruptive.

Support work is made of interruptions. You will get interrupted by alerts going off, integration partners emailing, people warning you of upcoming deploys, people needing help with something, people wanting reports taken from the production systems. In between this, you will want to try to get other work done, such as increasing the signal/noise ratio of the alerting system, cleaning up code, automating support processes, or updating support documentation. Which leads us on to:

The second problem: multitasking

Ordinary development work focuses on a single task at a time. Humans are bad multitaskers, particularly when it comes to complex tasks like development work. The context you store in your head when working on a feature gets lost when switching to another task.

In support work, multitasking is a fact of life. If a production alert goes off while you’re updating documentation, you have to stop writing and start fixing. When the alert is resolved, you may then have to schedule a post-mortem, before finally getting back to the documentation you were writing. Many of your tasks will require a small amount of effort, but will block on something external – such as sending off a certificate signing request to a CA, or waiting for a release to be signed off by the release manager before deploying it. In my experience, you’ll have three to six tasks in progress at any one time.

When on support, I’ve seen developers try to work on features in between interruptions. For the reasons listed here, this is a bad idea. Development work and interruptions work do not mix well. Development work requires a lot of context to be held in the head at once, and interruptions and task-switching are disproportionately more disruptive to development work than other kind of work.

The third problem: juggling priorities

In my experience as a developer, priorities are decided for us at our morning standup meeting. Everyone gets assigned to work on a story card for the day. If you finish a card, you pick the next one up off the backlog. It’s nice and simple, it requires almost no effort, and you don’t have to do it that frequently, so you can focus on writing code. There’s normally a product manager or business analyst whose job is worrying about priorities so that you can worry about getting work done.

In support work, new tasks can appear throughout the day: as user tickets, production alerts, or requests from colleagues. They will appear when you are in the middle of something else. Some of them will be less important than the task you are currently working on, so need to be captured and filed for later. Some will be more important, and so you will need to drop your current work to field the new task. You will need to make frequent snap decisions about whether or not to park the current task to work on the new urgent task, or to just capture and file it for later that day. Making frequent, rapid prioritization decisions – often with your head still in the context of some other task – is an alien experience to someone used to more typical development work.

The solution

If you want to have a good time as a developer on support, you are going to need a system of some sort. You won’t be able to keep track of all incoming tasks in your head, so you need a way to capture them. You also need a way of keeping track of tasks that are in progress but blocked on some external dependency or parked while a higher-priority task is performed. Importantly, your system must be very lightweight: it should be optimized for speed of the most common operations: task capture, prioritization, and identifying work in progress and blocked tasks. Speed is far more important than extensive features. I recently worked for a 5-day period on the GOV.UK support rota, during which my system recorded that I got through around 25 individual tasks. If my system were too heavyweight, I might spend as much time on task capture and prioritization as on real work!

Once you have rapid task capture and prioritization, then you may wish to think about capturing context: how much work has already been done on this task? Which source files need to be edited to fix this bug? Who am I waiting for a response from before I can continue working on this task? Not all tasks will require context recorded, but storing even a tiny amount of context can help manage a multitasking workload where tasks often get preempted by higher priority incoming tasks.

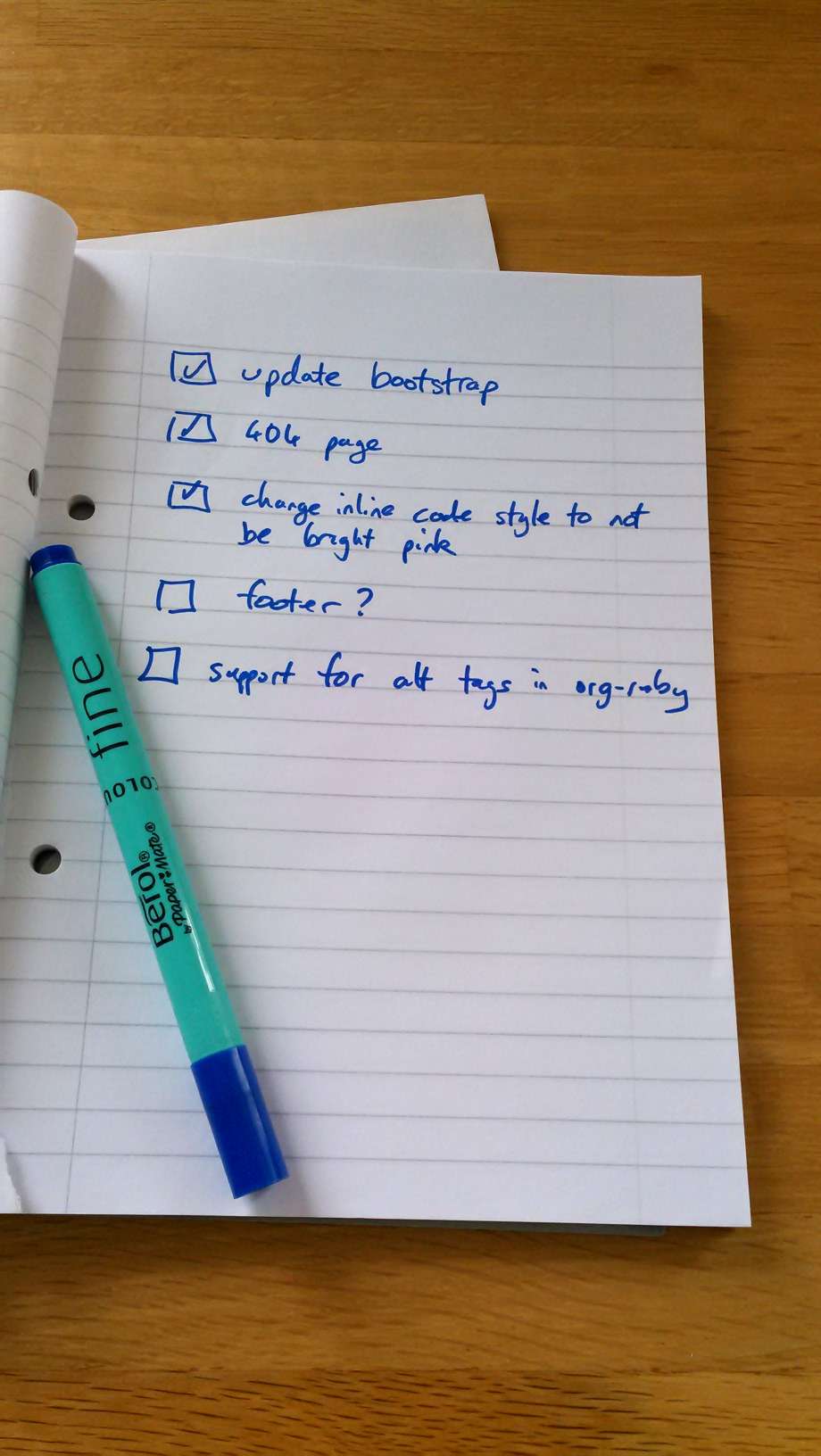

The simplest possible system is pen and paper. It supports efficient capture by scribbling a note down; it supports identifying work-in-progress by drawing a box by each item and ticking it when it gets done. Prioritization is not supported so well, as it’s not so easy to reorder items in a paper list than in some sort of digital form; but if the list doesn’t grow too big, this isn’t too much of a problem.

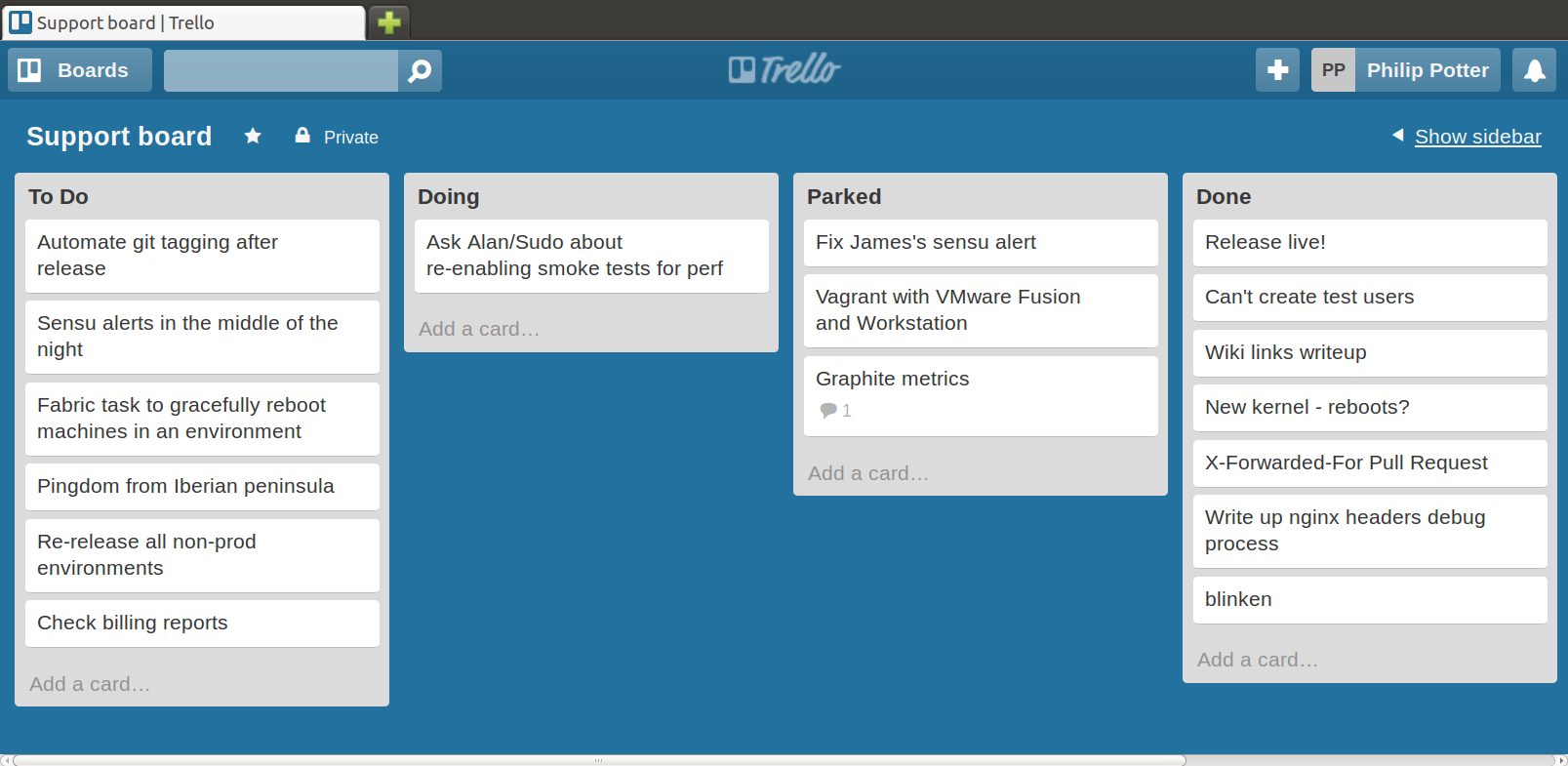

There are plenty of digital systems available too. Some people on my team have been using Trello to track support work. This has the added benefit that you can share the same trello instance between multiple people: useful if you have two or more support workers on the rota concurrently. It is supremely lightweight – task capture, tracking, and prioritization are all operations which take seconds rather than minutes.

I definitely wouldn’t use a more heavyweight project management tool such as JIRA for tracking tasks. Remember that you will normally be capturing new tasks as a result of an interruption while working on an existing task; the longer task capture takes and the more complex the workflow to capture a task, the more context you will lose on what you’re currently working on. Task capture in Trello is extremely fast: in JIRA, it’s both painfully slow, and takes you through multiple screens with screeds of options, requiring more focus to navigate through. Your system needs to be fast and lightweight.

Whatever system you end up with, it has to be one that works for you. Try something out, find out what works and what doesn’t, experiment with it by making changes, and keep reevaluating and iterating. For further ideas on evolving your system, the book Time Management for System Administrators is full of useful suggestions.