Philip Potter

-

Dad Weeknotes, volume 1

Posted on 13 January 2018

Last year I became a dad for the first time. A number of people I follow write weeknotes logging their work, and as my work is currently full-time dadding and people often ask me what it’s like, I thought I’d write some of it down. This is only half a week’s worth, but as it’s my first one it’s rather long anyway.

Context

This is, by some definitions, my first week as sole full-time parent of a baby. My wife, Sonia, and I took advantage of Shared Parental Leave, so we had the first three months together, then I returned to work for six months, and took another three months starting in December. However Sonia didn’t actually return to work until the start of January. As a result, this week is the first week where I’m truly in sole charge. Luke is now 10 months old, and when he turns a year I will return to work. So I’ve got 2 months of doing this.

That said, Sonia works from home. During my 6 months back at work, I worked from home 2 days a week and took Luke with me on my morning and afternoon breaks, to give Sonia a rest, and she is more than happy to return the favour.

Christmas and New year

Over the festive period, we hired a car for a month and drove all around the country visiting friends and family, with overnight stops in Shropshire, Cumbria, Glasgow, St Andrews, Berwick, and Lichfield (with extra day trips to Dunblane, Dundee, Edinburgh, and Hargrave in Northamptonshire). This was perhaps a slightly mad thing to do with a 9-month-old, but it turns out that hosts (and, especially, grandparents) will do a lot to accommodate tired and bedraggled parents and energetic babies.

Health

Luke is a healthy baby and is growing fast: he’s around the 90th percentile for both length and weight. (This means that of a typical sample of 100 babies, Luke would be longer and heavier than 90 of them, and lighter and shorter than 10 of them).

Luke does, however, have a cow’s milk protein allergy. His is the delayed or non-IgE form, which is not life-threatening, but it means he can’t have any dairy products in his diet, and this includes most standard infant formula. Conveniently, BBC radio’s Inside Health covered cow’s milk protein allergy this week (section starts from 07:20 in the programme).

The new routine

A question I sometimes get asked is “what do you do all day?” Here are some of the regular tasks:

Washing

On average, we do at least one load of washing a day, sometimes two. At this time of year, drying space is at a premium, so I spend a lot of time worrying about this, and trying to ensure that there’s always something drying.

Batch cooking

Luke is on solids (he started at 6 months old) and eats 3 meals a day. That food needs to come from somewhere. It’s just not practical to cook every meal from scratch, so we try to cook big batches of meals (often doubling the listed quantities in the recipe) and split into boxes for the fridge and freezer.

Along with this is planning and ordering the weekly shop, and making sure we have a good balance of nutrients for baby and ourselves for every meal. With Luke’s milk allergy, we generally try to make dairy-free meals that we can all have, rather than cook separate meals for Luke and for us.

Washing up

Feeding a baby results in an enormous amount of washing up. We have a dishwasher, which is a lifesaver, but there’s still a significant amount of stuff we wash by hand.

Feeding

Feeding Luke itself is hard work. Mostly we have a dish which we spoon-feed to Luke, with a few finger foods on the side such as quartered grapes, fingers of bread with peanut butter or houmous, sticks of pear or cucumber, etc. We have experimented with baby-led weaning (broadly, letting the baby feed themselves with surprisingly big chunks of food from a surprisingly early age). I find that spoonfeeding is labour-intensive, but gets more food actually inside Luke, and as he’s a big boy he gets very hungry. Letting him feed himself also means that the mealtime itself takes longer.

Luke has been getting more and more keen on feeding himself independently though, so we may need to adjust our strategy.

Forward planning

Babies change so fast, it’s hard to stay one step ahead of them. Luke started crawling a month ago, and shortly afterwards starting pulling himself up on sturdy things to a standing position. He also started pulling not-so-sturdy things on top of himself, so there’s a whole new class of hazards we need to watch out for, and a new round of baby-proofing. There are helpful books and online guides to warn us what is coming next, but it’s not always easy to find time to read them.

Some of the things we are going to be looking forward to:

- learning to stand and balance without holding on

- learning to walk holding one hand

- learning more syllables (Luke repeats single syllables at the moment such as “ba ba ba”)

- variegated babbling (ie, mixing syllables together, such as “ka da by ba mi doy doy”)

- assigning meaning to words

- learning to drink from an open cup

Reading

Luke, like most babies, loves to have stories read to him. Some of his favourites are:

- What a busy baby!

- Quentin Blake’s Ten Frogs

- Big Fish Little Fish

- Each Peach Pear Plum

- Usborne’s Noisy Orchestra

He’s not just seeing the pictures and hearing the language. He’s also learning to turn the pages himself, and learning to anticipate the next page.

Physical play

Since Luke has learned to crawl and to pull himself up to standing recently, he really wants to try it out all the time. He’s crawling all around the house and pulling on anything he can reach. This means he generally needs monitoring to make sure he doesn’t hurt himself or damage anything.

This is one of the toughest times for me. This is because it’s relatively boring – Luke is mostly directing his own play – so I feel I ought to be thinking about the next thing. I start planning the next meal, or folding some washing, or reading my calendar for the week ahead, and suddenly Luke has started reaching for the DVD player or the TV and I need to intervene.

Parent and baby groups

Being in a big city, there are loads of parent-and-baby groups available. These are good for parents to meet one another, to have a reason to get out of the house (which is often an achievement in itself), and for babies to get used to seeing others their own age.

For a while, I did a dad-and-baby yoga class in Herne Hill which I absolutely loved.

The week in brief

With all the context in place, my week might make some kind of sense now.

Tuesday

We returned from our christmas & new year road trip. We were exhausted. We put a wash on straight away, and got Luke’s bedtime equipment (including his plushy duckie comforter) unpacked straight away.

Wednesday

In the morning, we needed to return the car and take Luke to the dietician. Sonia took the morning off for this to work: I could have taken Luke with me when returning the car, but then I’d need to get Luke and car seat back by public transport which would have been awkward.

I did one wash on Wednesday.

Thursday

I had a grocery delivery arrive before 9am.

Our NCT group mums had a lunch together. It was good to catch up with them, some of whom I haven’t seen since my first three-month parental leave period.

Building a support network is important as a parent, to share tips, help each other out, and just provide emotional support. NCT has been a good way of making friends with people in the local area – prior to having a baby, it wasn’t too hard to rely on old friends distributed all across London, but having a baby makes you a lot less mobile.

It’s worth talking about gender for a minute here. There are two things working against me building my own support network. The first is that men are generally worse at maintaining close friendships, and this gets worse for men in long-term opposite-sex relationships who can tend to outsource relationship maintenance to their partner. This is something I have to be aware of and work on for myself.

The second is that men are seen by society as having less childcare responsibility - even in situations where they are clearly taking a childcare role. This means men can be overlooked or ignored in situations with parents of babies. See Friday for an example of this below.

(It may not surprise you to learn that my Christmas reading was How Not To Be a Boy by Robert Webb.)

I did two washes on Thursday.

I spent the afternoon making a massive batch of morrocan sweet potato soup, using ingredients from the grocery delivery. I chose the recipe as it has relatively little prep work - peel, chop, roast, blend. It’s also not terribly time-critical: I can be interrupted at almost any point and it’s okay. However, soups are necessarily spoonfeeding food, so I’m going to think about recipes which Luke can feed himself in future.

Thursday evening was orchestra rehearsal night. My orchestra ends at 10pm which is really late for me nowadays.

Friday

We are starting Luke at nursery soon. On Friday we went to a pre-admission session at the nursery. This was mostly going through application forms and policies. Sonia and I went together, and we shared the session with another mother and baby, but I really noticed how the nursery staff talked directly to the mums and not to me. One of the staff even forgot to introduce herself to me and ask me my name, after asking Sonia’s and Luke’s. It’s a small thing, and I didn’t complain, but I definitely noticed it.

I did one wash on Friday.

We managed to forget the required documents to give to the nursery so I had to make a return trip in the afternoon. On the way back I gave Luke a go on the swings, which he absolutely loves. His giant smile is so infectious!

I even managed to escape to go to GOV.UK Infrastructure’s goodbye drinks in the evening. I no longer take nights like this for granted, because someone needs to be in to keep an eye on the baby monitor. That said, it’s important for both Sonia and I to maintain some sort of social life, and so we talk a lot about what we can do to help each other go out in the evenings.

What is full-time dadding like, then?

Full-time dadding is hard work of a very particular sort. The main difficulty is that you don’t get to have a break on your own terms: there is often a constant stream of firefighting. Baby is hungry; baby is crawling around and needs watching; baby is threatening to pull furniture onto himself; baby wants a story. It can be difficult to even go to the toilet when you’re on your own with a baby, much less have a shower. One of the NCT mums talked about the multiple full cold cups of tea strewn around her house which she had made and then had no opportunity to drink.

That said, there are opportunities for breaks. Luke still has a nap in the morning and afternoon for ½–1½ hours (indeed, I’m writing these notes in his morning nap). But time management is important, and in fact some of the tips I picked up in Time Management for System Administrators are proving helpful, because fundamentally I’m responding to interrupts for much of my time.

There have been a few moments when I have been absolutely despairing and at my wit’s end. In my working life, I almost always have the opportunity of taking 10 minutes to go and have a coffee or a walk to let off steam, but often that’s just not the case with a screaming baby. I’ve had to learn new skills and techniques to manage my own emotional state and the baby’s. Often a walk is a good idea, as putting the baby in the pram or sling is a good way to calm them down when they’re fractious or upset.

I’m looking forward to writing more about my experiences!

-

Open for extension?

Posted on 23 September 2014

Suppose you’re writing Java, but because you don’t like pain all that much you’re using Google’s Guava library to make managing collections easier. You have a class which needs to return a concatenation of two lists, so you use Guava’s

Iterables.concat()static method:public class CertificateStore { private List<Certificate> myCertificates; private List<Certificate> partnerCertificates; public Iterable<Certificate> getCertificates() { return Iterables.concat(myCertificates, partnerCertificates); } }Now a consumer wants to add these certificates to an existing collection. So they try to use the

Collection.addAll()method:List<Certificate> certs = new ArrayList<>(); certs.add(otherCertificate); certs.addAll(store.getCertificates()); // ERROR!

The problem is that Collection.addAll() takes a Collection argument, not an Iterable. The frustrating thing is that

addAll()isn’t doing anything which requires a Collection instead of an Iterable: it’s just iterating through the elements of the collection, adding each one in turn.This is almost certainly because Collection was introduced in Java 1.2, but Iterable was only introduced in 1.5.

The functionality we want is implementable using only public methods of Collection, so you could write your own static method to do it, as Guava have with Iterables.addAll(Collection,Iterable). Then the consuming code would look like this:

List<Certificate> certs = new ArrayList<>(); certs.add(otherCertificate); Iterables.addAll(certs,store.getCertificates()); // okay now

This works, but uses a very different syntax. Guava’s extension to Collection just looks different. It’s not a first-class usage of Collection. It’s not obvious at a glance that certs is the thing being modified here.

What we ended up doing instead was this:

public class CertificateStore { private List<Certificate> myCertificates; private List<Certificate> partnerCertificates; public List<Certificate> getCertificates() { return ImmutableList.<Certificate>builder() .addAll(myCertificates) .addAll(partnerCertificates) .build(); } }By returning a List instead of an Iterable, we could use

Collection.addAll()directly, resulting in clean, consistent code for the consumer, at the cost of slightly more verbose (and slightly less efficient) code on the producer side.

What this example demonstrates is that being open for extension isn’t just about what’s possible. It’s also about making extensions look just like the code they are extending. Users will know the core language features and libraries; code that doesn’t resemble those will add a roadblock to readability.

The obvious fix to this problem is to allow people to extend classes with their own method, a practice known in the Ruby community as monkey-patching. This is undesirable for a number of reasons: methods are not namespaced, so if two different consumers of a library create a method with the same name, they will conflict; further, monkey-patching often allows access to private internals of a class, which is not what is wanted here.

Let’s imagine what the example would look like using Clojure’s protocols. Suppose I am using a Collection protocol, with an

addfunction but noaddAllfunction at all:(defprotocol Collection (add [c item]) ;;... other methods )

Now I want to add all elements from a Java Iterable to my collection. If I wrote the code out in full, it might look like this:

(def certs (create-list)) ;; implements Collection protocol (add certs other-certificate) (doseq [cert (seq (get-certificates store))] (add certs cert))

If I want to define a function to encapsulate this iteration, it might look like this:

(defn add-all [coll items] (doseq [item (seq items)] (add coll item)))And now, my consuming code looks like this:

(def certs (create-list)) (add certs other-certificate) (add-all certs (get-certificates store))

There’s no visual difference between the core protocol function

add, and my extension functionadd-all. It’s as if the protocol has gained an extra feature. But because my extension is an ordinary function, it is namespaced. If we add explicit namespaces in, it might look like:(ns user (:require [collection.core :as c] [iterable.core :as i])) (def certs (c/create-list)) (c/add certs other-certificate) (i/add-all certs (get-certificates store))Namespaces are a honking great idea! And in this case, my extension is namespaced, so even if someone else does the same (or a similar but incompatible) extension, there won’t be a name collision.

Clojure’s protocols aren’t unique in being open for extension in a transparent way. Haskell’s typeclasses and the Common Lisp Object System (CLOS) both also exhibit this feature. Being open for extension isn’t enough, if your extensions look like warts when placed next to core code. Extensions should be as beautiful as the code they extend.

-

Some gluten-free baking recipes

Posted on 13 September 2014

Just baked this afternoon: two gluten free baking recipes. Both turned out amazingly, so I had to document them for posterity!

Gluten-free nankhatai

These are almond biscuits spiced with a heavy dose of cardamon.

This is based on this recipe. It’s awkward because the ingredients are measured in cups, whereas I much prefer to measure by weight, particularly for baking.

Ingredients:

- 50 g gram flour

- 100 g ground almonds

- 10 g cardamom pods

- pinch of salt

- 75 g icing sugar

- 110 g butter

- almonds to garnish

For this recipe, I bought flaked almonds (ie thinly sliced almonds) and chopped them up in a food processor. This resulted in a delightfully irregular texture in the final product.

Grind the cardamom with a mortar & pestle, sift with the gram flour and add the ground almonds and salt. Cream the butter and sugar together, then mix in the dry ingredients and knead. Put in the fridge for 15 minutes.

Take the dough out, make into 16 small balls and put onto a greased baking tray. These balls will spread out during cooking so give them plenty of elbow room! Put a flake of almond on each and press gently. Put the baking tray back into the fridge for a further 15 minutes.

Bake at 150℃ for around 20 minutes, taking care to ensure they don’t turn brown. Place on a cooling rack for 10 minutes. They will still be very soft when you take them out of the oven, but they will firm up as they cool.

As you can see, we were stuck with a baking tray that was far too small and our nankhatai soon invaded each others’ personal space. It didn’t stop them being delicious though!

Gluten-free banana bread

For this, we followed this recipe but with two substitutions:

- instead of cherries and sultanas, we used figs

- instead of rice flour, we used gram flour

It worked an absolute treat – would definitely do again. It was good to have two recipes to use up the gram flour.

-

Being a developer on support

Posted on 31 August 2014

One of the things that gets talked about a lot in the devops world is that developers should support the applications that they build. However, something I’ve seen is developers getting severe culture shock from their first experience of support. Support work is a totally different style of work from ordinary development, and there’s often little or no explanation or instructions as to what you should be doing, and how you should do it.

The first problem: interruptions

Ordinary development work eschews interruptions. You work on hard problems that often don’t have immediately obvious solutions (or worse, have immediately obvious wrong solutions). You may need to go through several iterations of design before finding one that solves the problem adequately. You hold a lot of context in your head, so an interruption can be incredibly disruptive.

Support work is made of interruptions. You will get interrupted by alerts going off, integration partners emailing, people warning you of upcoming deploys, people needing help with something, people wanting reports taken from the production systems. In between this, you will want to try to get other work done, such as increasing the signal/noise ratio of the alerting system, cleaning up code, automating support processes, or updating support documentation. Which leads us on to:

The second problem: multitasking

Ordinary development work focuses on a single task at a time. Humans are bad multitaskers, particularly when it comes to complex tasks like development work. The context you store in your head when working on a feature gets lost when switching to another task.

In support work, multitasking is a fact of life. If a production alert goes off while you’re updating documentation, you have to stop writing and start fixing. When the alert is resolved, you may then have to schedule a post-mortem, before finally getting back to the documentation you were writing. Many of your tasks will require a small amount of effort, but will block on something external – such as sending off a certificate signing request to a CA, or waiting for a release to be signed off by the release manager before deploying it. In my experience, you’ll have three to six tasks in progress at any one time.

When on support, I’ve seen developers try to work on features in between interruptions. For the reasons listed here, this is a bad idea. Development work and interruptions work do not mix well. Development work requires a lot of context to be held in the head at once, and interruptions and task-switching are disproportionately more disruptive to development work than other kind of work.

The third problem: juggling priorities

In my experience as a developer, priorities are decided for us at our morning standup meeting. Everyone gets assigned to work on a story card for the day. If you finish a card, you pick the next one up off the backlog. It’s nice and simple, it requires almost no effort, and you don’t have to do it that frequently, so you can focus on writing code. There’s normally a product manager or business analyst whose job is worrying about priorities so that you can worry about getting work done.

In support work, new tasks can appear throughout the day: as user tickets, production alerts, or requests from colleagues. They will appear when you are in the middle of something else. Some of them will be less important than the task you are currently working on, so need to be captured and filed for later. Some will be more important, and so you will need to drop your current work to field the new task. You will need to make frequent snap decisions about whether or not to park the current task to work on the new urgent task, or to just capture and file it for later that day. Making frequent, rapid prioritization decisions – often with your head still in the context of some other task – is an alien experience to someone used to more typical development work.

The solution

If you want to have a good time as a developer on support, you are going to need a system of some sort. You won’t be able to keep track of all incoming tasks in your head, so you need a way to capture them. You also need a way of keeping track of tasks that are in progress but blocked on some external dependency or parked while a higher-priority task is performed. Importantly, your system must be very lightweight: it should be optimized for speed of the most common operations: task capture, prioritization, and identifying work in progress and blocked tasks. Speed is far more important than extensive features. I recently worked for a 5-day period on the GOV.UK support rota, during which my system recorded that I got through around 25 individual tasks. If my system were too heavyweight, I might spend as much time on task capture and prioritization as on real work!

Once you have rapid task capture and prioritization, then you may wish to think about capturing context: how much work has already been done on this task? Which source files need to be edited to fix this bug? Who am I waiting for a response from before I can continue working on this task? Not all tasks will require context recorded, but storing even a tiny amount of context can help manage a multitasking workload where tasks often get preempted by higher priority incoming tasks.

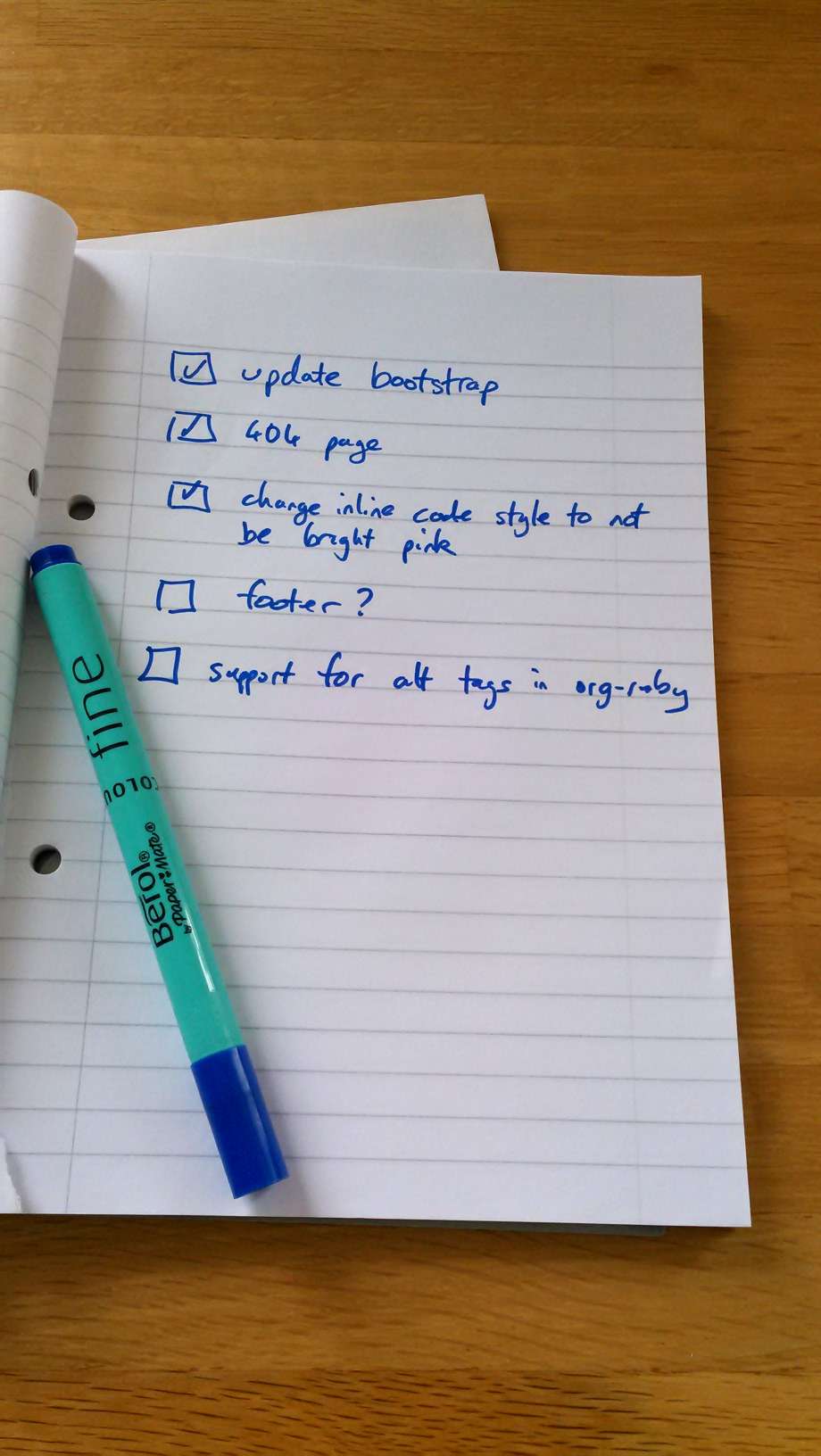

The simplest possible system is pen and paper. It supports efficient capture by scribbling a note down; it supports identifying work-in-progress by drawing a box by each item and ticking it when it gets done. Prioritization is not supported so well, as it’s not so easy to reorder items in a paper list than in some sort of digital form; but if the list doesn’t grow too big, this isn’t too much of a problem.

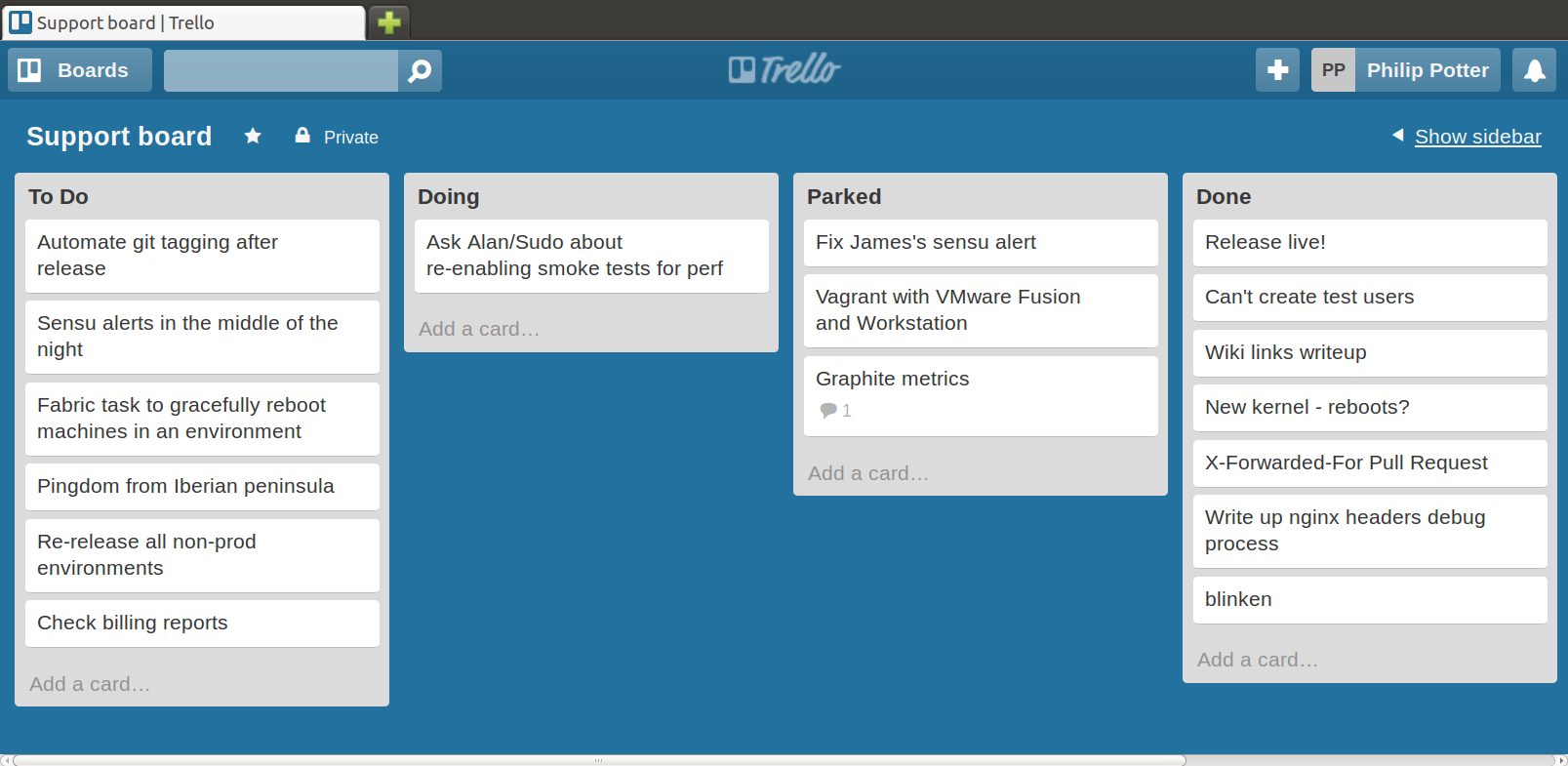

There are plenty of digital systems available too. Some people on my team have been using Trello to track support work. This has the added benefit that you can share the same trello instance between multiple people: useful if you have two or more support workers on the rota concurrently. It is supremely lightweight – task capture, tracking, and prioritization are all operations which take seconds rather than minutes.

I definitely wouldn’t use a more heavyweight project management tool such as JIRA for tracking tasks. Remember that you will normally be capturing new tasks as a result of an interruption while working on an existing task; the longer task capture takes and the more complex the workflow to capture a task, the more context you will lose on what you’re currently working on. Task capture in Trello is extremely fast: in JIRA, it’s both painfully slow, and takes you through multiple screens with screeds of options, requiring more focus to navigate through. Your system needs to be fast and lightweight.

Whatever system you end up with, it has to be one that works for you. Try something out, find out what works and what doesn’t, experiment with it by making changes, and keep reevaluating and iterating. For further ideas on evolving your system, the book Time Management for System Administrators is full of useful suggestions.

-

London emacs meetup, 20th May 2014

Posted on 21 May 2014

Last night was the second London emacs meetup. Here are my rough-and-ready notes, taken in org-mode, like all my notes.

emacsspeak: emacs for visually impaired people

- http://emacspeak.sourceforge.net

- anecdote: a friend went blind and emacspeak saved his career

intro, @bodil & @dotemacs

- welcome!

- format:

- one or two short talks

- about things that are useful for all emacs users

- then afterwards, gather around particular fields of interest

talk: writing major modes (by @dotemacs)

intro

- last time, @bodil gave a talk

- definition:

- “encapsulating a set of editing behaviours”

- book: GNU Emacs Extensions, O’Reilly

- Yukihiro Matsumoto (matz)

- “I started Ruby development with influence from emacs implementation”

- “but as an emacs addict I needed a language mode”

- “auto-indent was a must”

- “back in 1993, there was no auto-indenting language mode for a language with such syntax”

- “If I couldn’t make ruby-mode work, the syntax of ruby would have become more C-like”

- Bob Glickstein & Scott Andrew Borton

modes

- two types: major & minor

(define-minor-mode ...)- keymap (specific for the minor mode)

- variable

<name>-mode - command called

<name>-mode- toggles the mode

- add it to a hook

(add-hook 'some-mode 'your-mode)

- major mode:

- memorable name :)

- hooks (

<name>-mode-hook) - syntax table

- defines how things should appear (highlighting)

- entry function (

<name>-mode) - syntax highlighting; two options:

- optimized regexes

- Q: what does “optimized” mean here?

- eg matching keywords would mash together into a mega-regexp

- Q: what does “optimized” mean here?

- use regexp-opt

- takes a list of strings, and outputs a regexp which matches all of those things

- aside:

rxmodule compiles sexps to regexes

- optimized regexes

- indentation

- syntax table “behaviour” & movement

- how you jump between functions, classes, & other constructs the language has

- remove all buffer-local variables

- set the variables

major-modeto<name>-modemode-nameto string “name”

- keymaps; two options:

- sparse-keymap

- suitable for up to half a dozen

- define your own, otherwise

- sparse-keymap

- bind mode to files

(add-to-list 'auto-mode-alist '("\\.bar" . foo-mode))

- run user defined hooks for the mode

- defined with

<name>-mode-hook

- defined with

- provide mode

(provide '<name>)

- cookies

;;;###AUTOLOAD

- “this sounds like a lot of work, why reinvent the wheel”?

- cookie cutters

sample-mode(available on emacswiki)derived-mode(part of emacs)

- cookie cutters

- checkdoc

- good tool to run once you have defined a mode

- kind of a lint tool

- ecukes

- framework that allows you to write tests in:

- espuds

- step definitions

questions:

- keybinding conventions?

- Who gets to claim the C-c space?

- it’s really complicated

- there’s seven or eight layers

- minor modes override major

- C-x normally reserved by emacs

- C-c C-<something> major mode generally

- C-c <something> own use (shouldn’t be modes)

- super and hyper of course

- windows key & os x command

- why do I get so many compilation warnings when installing modes through package-install?

tangent: eshell

- written by someone working on windows and didn’t have a decent shell

- redirecting straight into a buffer is nifty

- all interactive commands are bound as shell commands

- Plan9 features built in

tangent: testing

- why use ecukes and espuds?

- why can’t I just do my testing in a repl?

- you’ll have to restart your emacs a lot because your tests will be messing global mutable state

- automating a test suite would make things more convenient than manually using C-x C-e

- why can’t I just do my testing in a repl?

- is there a good mode for editing these tests?

- you could use cucumber-mode

- is there a way to jump to the step-definitions?

- is there something between cucumber and C-x C-e for testing?

ert- see dotemacs/ipcalc.el for an example

- is there a way to test keybindings without using ecukes?

- ecukes has the most momentum (seemingly)

- dash.el does tests nicely

- the README has some examples which are the unit tests

- see magnars/dash.el

tangent2: magnars emacsrocks talk

ideas for bird of feather groups

- highlighting (first)

- multiple emacs woes (OS-supplied vs emacs 24)

- eshell (dotemacs)

- bulletproof emacs for the lightweight users (mickey)

- sql in emacs (mickey)

- org-mode (everyone later)

- org-reveal?

- haskell (later)

- flymake/flycheck

- jfdi (apart from java)

- need to be aware of the lang-specific linter you need

making the most of paredit/smartparens (bodil)

from earlier discussion

- “I made paredit work for python!”

- comparison

- paredit works out of the box

- smartparens configurable to work in any mode

- paredit for haskell!

bodil’s config

- bodil-smartparens (find it on github.com/bodil )

- make smartparens behave as much like paredit as possible

- turn on smartparens-strict-mode in your lisp mode hook

- paredit’s M-<up> and M-r (splice-sexp-killing-backward and raise)

- both useful for pulling expressions out of let bindings

- bodil: I’d actually recommend paredit for lisps, but smartparens

is useful for other langs

- I’m actually using it for haskell

- html tagedit – like paredit for html

- syntax-aware killing

- slurp and barf

- magnar again :)

- autoindent in curly-brace languages

- ie when pressing RET in

function(){|} - want to create new line indented, with curly brace on line following that

- ie when pressing RET in

- structural-haskell mode

- sort of like paredit for haskell syntax

eshell

- interactive commands available as regular shell commands (eg find-file)

- lots of commands replaced with emacs-friendly modes (eg man)

- can work with tramp (eg

cd /sudo::/etc; find-file passwd) - configuration goes in

emacs.d/eshell- in particular aliases in

emacs.d/eshell/aliases

- in particular aliases in

- buffer redirection

- use C-c M-b to select and insert a reference to a buffer

- for example:

echo foo >> #<buffer *scratch*>

- plan 9 features

tangent: webkit.el

- takes an external webkit window and puts it on top of the appropriate emacs window

tangent: fish

- why fish?

- sick of bash

- completion is really cool